Long-billed Dowitcher

General Description

The Long-billed Dowitcher is very similar in appearance to the Short-billed Dowitcher. Both birds are medium to large shorebirds. In breeding plumage, they are reddish underneath and mottled brown above. In flight, they show a pale trailing edge on their wings and a distinctive white blaze up their backs, which easily identifies them as dowitchers. The distinction between the two species is not as simple. The female of both species has a longer bill than the male, and the bill of the female Short-billed is the same length of that of the male Long-billed, so bill length can be confusing. The Long-billed in breeding plumage usually has some barring rather than spotting on the side of its breast in front of the wing. The Short-billed is usually spotted. The belly of the Long-billed is typically reddish all the way back, while the Short-billed often has some white on its belly. The juvenile Short-billed is brighter than the Long-billed, with light edging on its feathers. The Short-billed juvenile has bright edging and internal markings on the tertial feathers. The Long-billed juvenile is drabber and darker than the Short-billed. Non-breeding plumage is very difficult to distinguish. Range, habitat, and vocalizations should all be used to help distinguish between these two species.

Habitat

During migration and winter, Long-billed Dowitchers are usually found on fresh water marshes and sometimes in coastal areas. They are often found on drying lakeshores. In coastal habitats, they are usually in small pools with salt-marsh vegetation. They breed farther north and west than Short-billeds, in grass- or sedge-dominated tundra marshes in Arctic coastal regions in Alaska.

Behavior

Long-billed Dowitchers are usually found in smaller flocks than Short-billeds, but huge flocks of Short-billed Dowitchers often include a few Long-billed Dowitchers. Long-billed Dowitchers feed by probing their long bills into mud or shallow water. Their bills are full of nerve endings, useful for sensing prey. They walk along slowly, lifting their heads up and down like a sewing machine. The call is a high peeping sound, usually a single call, but sometimes repeated.

Diet

On the breeding grounds, Long-billed Dowitchers eat insects and insect larvae. On mudflats they also eat mollusks, crustaceans, marine worms, and other aquatic invertebrates.

Nesting

Long-billed Dowitchers usually nest on the ground near water. The nest itself is a fairly deep scrape in a clump of moss or grass, lined with sedge or grass. The bottom of the nest is often damp. Both parents incubate the four eggs for 21 to 22 days. The young leave the nest within a day of hatching and find their own food. Both parents help tend the young at first, but the female may abandon the group soon after they hatch. The male probably stays with the young until they are close to fledging at 20-30 days. Each pair raises a single brood per year.

Migration Status

Long-billed Dowitchers migrate medium distances, not as far as Short-billeds. They come through Washington later in the fall than their shorter-billed relatives, and they winter along the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts. Some first-year birds stay on the wintering grounds in summer.

Conservation Status

Until 1950 Short-billed and Long-billed Dowitchers were considered a single species. The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the population of Long-billed Dowitchers at 500,000. While they are not abundant anywhere in Washington, they are fairly common and widespread. Over-hunting contributed to declines in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but protection from hunting has resulted in a rebound. Range-wide, the number of migrants has increased, and the breeding population has recently expanded into Siberia. It is not fully understood whether this is a shift from other nesting areas, or a true expansion. Habitat loss and environmental contaminants also threaten the current population of Long-billed Dowitchers.

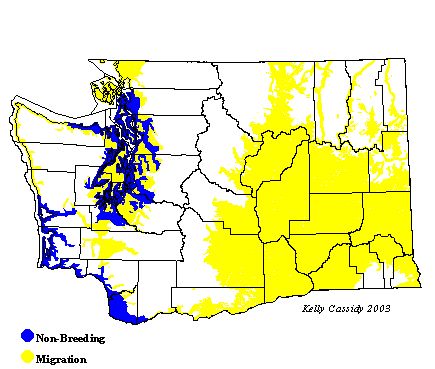

When and Where to Find in Washington

The Long-billed Dowitcher is less common during migration than the Short-billed Dowitcher, but is the more common winter resident in major estuaries on the Washington coast and in Puget Sound. It is generally absent from eastern Washington in winter. Coastally, the first adult migrants start arriving from the north in July and are common from July into mid-September. Juveniles start migrating through in mid-August and are common through October. They are uncommon from November through April. The spring migration is short, and birds are common for only a few weeks in the beginning of May. They taper off to uncommon in late May, and by June they are reported only occasionally. In eastern Washington, they are rare in late June, but quickly become common in July and remain so through October. They are uncommon in November, rare in December, and only occasionally spotted from January through March. In April, numbers start migrating through again, but they are still uncommon. The migration builds in May, and they are common for most of that month. This is a short period, and by the end of May they are uncommon, and by the second half of June they are rarely reported.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | F | F | U | F | F | F | U | U | |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| West Cascades | F | F | U | |||||||||

| East Cascades | R | U | F | U | ||||||||

| Okanogan | R | R | U | F | F | |||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | R | |||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | U | C | C | C | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius